1. What we want, and how we'll get it.

What do we want in our school? Well, we want love — of learning, and of community. We want mastery — of skills, and of self. And we want wisdom — a understanding of big-picture complexity.

Computers can't bring us to these goals: only loving, skillful, and wise humans can. But they can help.

Our school needs to position itself between two extreme camps in educational reform: call them the "hi-tech" and "Waldorf" camps.

The "hi-tech" people talk as if computers in classrooms will bring the messianic age. In my estimation, this is sheer silliness. (Actually, I wonder if these people even believe their own rhetoric.) In fact, technology in classrooms poses real, often-ignored dangers: computers employed poorly can distract students.

On the other side, the Waldorf people talk as if banning computers is the only smart course. I'll admit that my basic prejudices are with this side, but it seems clear to me that computers (and screens more generally) can play a big role in helping us achieve the schools we dream of.

We need to synthesize the best insights of the pro-tech and Waldorf positions.

Alas: I have no idea what that brilliant synthesis is. Consider this post as my way to move, haltingly, toward it.

2. Age of Distractions

So, the question is: What place should screens have in our school? ("Screens" here means desktops, laptops, tablets, e-readers, smart phones, TVs, and projectors.)

Any attempt to answer this needs to start with a diagnosis of our modern situation:

We're surrounded by machines which can help us do things that were never before possible — and which are very distracting.

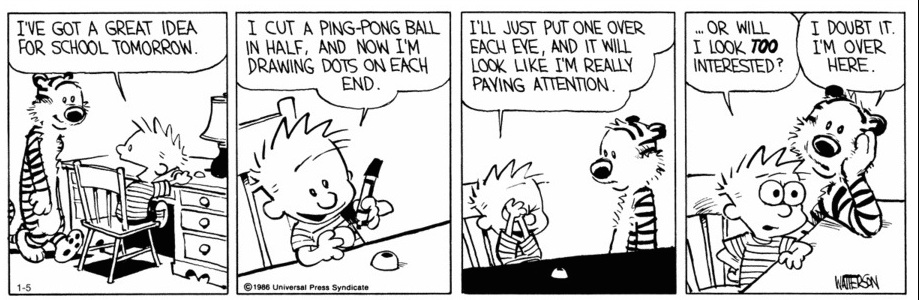

To put that in economic terms: we live in the middle of an arms race for our (and our students') attention. This battle is well-funded, and its major combatants don't hesitate to exploit our base instincts —

Bright, glowing things grab our attention. Bite-sized nuggets of information grab our attention. All things instant grab our attention.

The modern glowing rectangles that we surround ourselves with — now combined with social media — are brilliantly constructed to grab our (and our students'!) attention.

Distraction isn't necessarily bad. I'm no kill-joy. In fact, I hope that I'm the opposite of a kill-joy: the problem with schools is that they're too lifeless, too pointless, to unpleasurable.

It's no wonder that people turn to screens to bring happiness into their lives: distractions, obviously, can be wonderful! (Sci-fi novels are a personal favorite distraction. They're my self-medication for chasing away the occasional blues.)

Distractions are good when they whisk us away from situations that are both unpleasant and unhealthy.

Distractions become dangerous, though, when they take us out of situations that are healthy and hard.

If we succeed in our goals for this school, it will be healthy and hard: we'll be leading kids to train their minds and bodies, to explore the world that existed before them and imagine the world that will exist after them, to ask the big questions of human life.

These things will be pleasurable: we're striving to make a school for human flourishing. But that doesn't mean that every one of the things kids do will be pleasant in the short-term. Deep learning can be frustrating, even painful. And when it is, students (and faculty) will be prey to distractions — specifically, to other tasks that are more gratifying in the moment, but less wonderful long-term.

Call it the algebra / Angry Birds divide. Algebra: pleasant long-term (say, from the ability to grok abstract patterns, and be accepted to college), sometimes not so pleasant in the short-term (say, after running my head against multinomial division for the fourth time, and failed).

Angry Birds: pleasant in the short-term, but of less pleasure in the long-term.

In the short term, Angry Birds will win out every time. And we only live in the short term.

Pause for a brain science moment! This tendency to obey present whims more than future rewards, dubbed "temporal discounting" in the classy argot of researchers, is one of the better-attested facts of human psychology, and also (as Gary Marcus argues in his wonderful book Kluge) of vertebrate psychology more generally. It's a weakness built deep into the human brain. If ours is a school that takes human nature seriously, we need to take this seriously, and plan accordingly.

Which is all to say: we're surrounded by technology that takes advantage of some of our inbuilt weaknesses. We should be cautious about this.

3. Personal Screens in the Upper Grades

Clay Shirky, bald celebrity theorist of social media (and professor at NYU), recently caused a stir in schooling circles by reporting that he's banned screens in his course on the Internet.

This is the sort of prattle you'd expect from an anti-tech curmudgeon. That it's coming from one of the Internet's major cheerleaders is the surprising bit.

Shirky reports that his decision came gradually, and grudgingly. (If you haven't already read his essay at medium.com — "Why I Just Asked My Students To Put Their Laptops Away" — you'll very much want to!)

He noted that the distraction seemed to be building, as more personal technology entered the classroom:

the practical effects of my decision to allow technology use in class grew worse over time. [all emphases mine] The level of distraction in my classes seemed to grow, even though it was the same professor and largely the same set of topics, taught to a group of students selected using roughly the same criteria every year. The change seemed to correlate more with the rising ubiquity and utility of the devices themselves, rather than any change in me, the students, or the rest of the classroom encounter.

He found, too, that his occasional requests to put the technology away for a time seemed to bring more relief than disgruntlement:

I’ve noticed that when I do have a specific reason to ask everyone to set aside their devices (‘Lids down’, in the parlance of my department), it’s as if someone has let fresh air into the room. The conversation brightens, and more recently, there is a sense of relief from many of the students.

His decision to switch from a policy of "allowed unless by request" to one of "banned unless required" had two reasons.

First, he realized that the basic conflict isn't between students and teachers, but between students and themselves. His students typically want to pay attention, typically want to learn, but find doing that hard to do. Shirky explains:

Jonathan Haidt’s metaphor of the elephant and the rider is useful here. In Haidt’s telling, the mind is like an elephant (the emotions) with a rider (the intellect) on top. The rider can see and plan ahead, but the elephant is far more powerful. Sometimes the rider and the elephant work together (the ideal in classroom settings), but if they conflict, the elephant usually wins.

Haidt's metaphor, recall, is central to our conception of good schools. We want to be a school for elephants and for riders. Shirky continues:

After reading Haidt, I’ve stopped thinking of students as people who simply make choices about whether to pay attention, and started thinking of them as people trying to pay attention but having to compete with various influences, the largest of which is their own propensity towards involuntary and emotional reaction. (This is even harder for young people, the elephant so strong, the rider still a novice.)

Shirky's calling his college students young — and he's right. But we'll be working with six-year-olds! What's true for his students may be even more true for ours.

Regarding teaching as a shared struggle changes the nature of the classroom. It’s not me demanding that they focus — it’s me and them working together to help defend their precious focus against outside distractions.

That line might be one I commit to memory. We can't afford a romantic view of students — we need to be realistic about their cognitive limitations. We need to be willing to be somewhat paternalistic in order to help them live up to their ideals.

And while I [teach], who is whispering to the elephants? Facebook, Wechat, Twitter, Instagram, Weibo, Snapchat, Tumblr, Pinterest, the list goes on, abetted by the designers of the Mac, iOS, Windows, and Android. In the classroom, it’s me against a brilliant and well-funded army…. The industry has committed itself to an arms race for my students’ attention, and if it’s me against Facebook and Apple, I lose.

If it's our faculty versus an army of app designers, we'll lose. And the students can't help it — it's their basic psychology working against them. We need to help students help themselves.

This was the first insight Shirky had that made him adopt a less libertarian policy of in-class technology use. The second was that when one student uses a distracting technology, many other students may be distracted.

He cites a study with the alarming title "Laptop Multitasking Hinders Classroom Learning for Both Users and Nearby Peers":

We found that participants who multitasked on a laptop during a lecture scored lower on a test compared to those who did not multitask, and participants who were in direct view of a multitasking peer scored lower on a test compared to those who were not. The results demonstrate that multitasking on a laptop poses a significant distraction to both users and fellow students and can be detrimental to comprehension of lecture content.

Shirky summarizes:

There is no laissez-faire attitude to take when the degradation of focus is social. Allowing laptop use in class is like allowing boombox use in class — it lets each person choose whether to degrade the experience of those around them.

There's one thing that Shirky conspicuously doesn't mention in his essay: the effect of students' personal tech on their teachers. I assume he leaves this out because he's striving to come off as a likable guy. Or, I don't know, maybe it's because he's just crazy-unflappable.

I don't have either limitation, so I'll state this plainly: student tech can be horribly distracting for us teachers.

Maybe this is because I'm ADHD? (If so, that doesn't excuse the problem: we'll have other teachers who live on the ADHD side of humanity.) Maybe this is because I hate rudeness? (Well, ditto.)

Either way, if we want to hang onto our wonderful teachers, we need to be as kind to them as possible.

Teaching is a damned hard job.

And when a teacher has poured hours into researching a topic, has put their soul into making the topic clear and compelling, it's not kind to them to allow students to interrupt everything by getting pinged by Facebook.

4. Computers in the classroom.

Our school needs to, once again, position itself between the extremes of the pro-technology and anti-technology camps in education. But so far, I probably sound like some crazy person, rattling on (as I am) about the dangers of personal screen use among the kids these days.

Fair enough!

I sound, in other words, like a Waldorf teacher.

Waldorf schools, for those who don't know, grew out of the ideas of Austrian educator and philosopher Rudolf Steiner. They were launched in Europe after the close of the First World War as an attempt to create a wiser, more caring society that wouldn't destroy itself in an orgy of violence. (Would that they would have succeeded more fully in that…)

My love of Waldorf schools is qualified — I think they get some important things wrong — but I am zealous for some of their ideals: developing empathy, cultivating artistic skills, and promoting play — all without shucking aside the vision of an intellectual curriculum.

(For more on Waldorf schooling, positive and questionable, check out its Wikipedia page.)

And Waldorf schools shun technology. No computers, or screens of any kind, in the school.

Well, maybe that's not surprising: hippie schools, and all that. What might be surprising is that this anti-technological stand is popular in Silicon Valley, or at least so the New York Times reports.

In Matt Richtel's "A Silicon Valley School That Doesn't Compute" (clever pun there, Mr. Richtel), we learn:

The chief technology officer of eBay sends his children to a nine-classroom school here. So do employees of Silicon Valley giants like Google, Apple, Yahoo and Hewlett-Packard.

But the school’s chief teaching tools are anything but high-tech: pens and paper, knitting needles and, occasionally, mud. Not a computer to be found. No screens at all.

The counterintuitive shock of this is similar to the "tech prof bans tech" example above. If a school in, say, Gambia lacks computers, it's not news. If a school in Silicon Valley lacks computers, it's news.

More:

While other schools in the region brag about their wired classrooms, the Waldorf school embraces a simple, retro look — blackboards with colorful chalk, bookshelves with encyclopedias, wooden desks filled with workbooks and No. 2 pencils.

Here's where the word I've been using — "technology" — becomes problematic: blackboards are technology. So are encyclopedias, desks, and pencils. (At one point, each of these was the leading, bleeding edge of technology — the innovation that was ballyhooed to transform the world!)

A school can't ban technology, because schooling itself (along with all the parts that make it up) is a technology.

But unlike glowing screens that transport a single individual away from the substance of learning, these technologies are the substance of learning.

Waldorf parents argue that real engagement comes from great teachers with interesting lesson plans.

'Engagement is about human contact, the contact with the teacher, the contact with their peers,' said Pierre Laurent, 50, who works at a high-tech start-up and formerly worked at Intel and Microsoft. He has three children in Waldorf schools, which so impressed the family that his wife, Monica, joined one as a teacher in 2006.

Education is a human-thing: obviously, an idea that's in harmony with our nascent school!

And yet, and yet: I suspect the Waldorf schools are going too far. Or let me reel that back, and only speak to our school: I think that we can achieve even better results by bringing in some modern technology with care.

Computers (and modern media more generally) let us do things that would be impossible otherwise. We'll use screens to accomplish what would otherwise be miraculous.

- We'll watch the subtle flapping of a great white shark as it launches itself out the water to pursue a seal — in slow motion.

- We'll hear the hooting, howling, and whooping of the central African Wodaabe tribe as they perform their competitive courtship dances.

- We'll savor old films, entering the imaginations of some of humanity's greatest storytellers.

- We'll luxuriate in beautiful music.

- We'll immerse ourselves in paintings and photography.

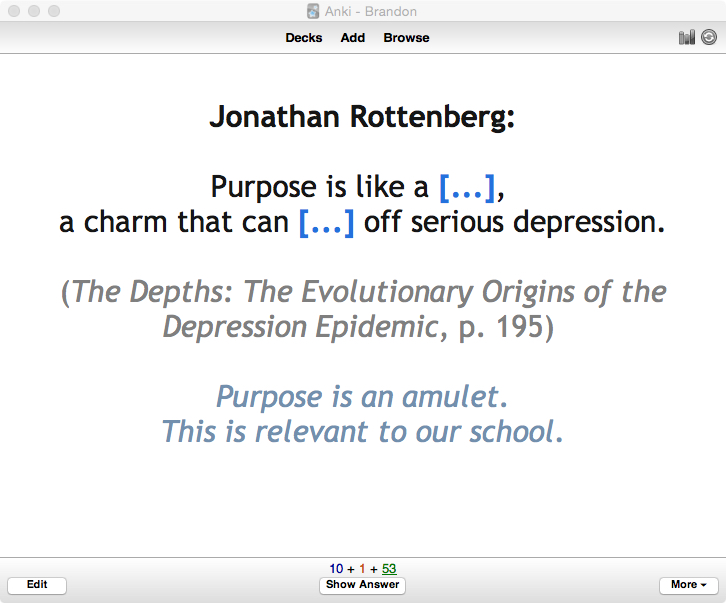

- And we'll Google questions, and learn coding, and create databases of our favorite ideas and quotes.

These are miracles. These go beyond anything schools could have done a century ago — or even a decade ago.

5. So:

We can create the best schools that the world has seen. We can have classrooms that bring students into delight, meaning, and long-term, collective flow states.

On the one hand, this will require being careful of what distractions that we let students bring in.

And on the other, this will be helped by using technology to disport us to places that we couldn't otherwise reach.