A problem:

Without hope of finding answers, posing ever-more questions can be miserable.

Though you wouldn't know this to read a lot of us educators — as a tribe, we're prone to praising asking questions, and to demean finding answers. (I sometimes hear the quote by Rilke: "Love the questions themselves" used to this end.)

But answers are thrilling. Finding answers is the goal of asking questions.

Don't get me wrong: I love mystery. Love love love it. But I love true mystery: the sort that comes from questions that elude even my best attempts to answer.

If our schools revolve around a curriculum of question-asking, we need to match it with a curriculum of question-answering.

Our basic plan:

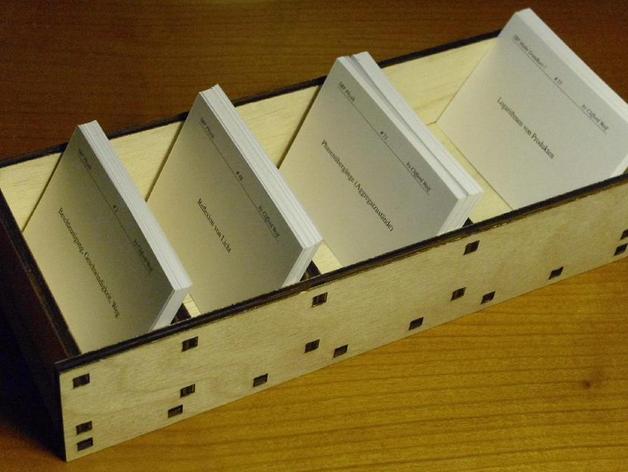

As stated in my last post, our students will collect questions in their personalized commonplace books. These questions can be of any sort — philosophical, scientific, mathematic, historical — anything. Once a week our classes will choose a few questions to pursue more deeply.

Then they'll decide how they want to hunt for answers. There are three things (at least) our students could decide to do with a question.

- Write the question on our chalk wall. Our classrooms could have one wall (or a section of a wall) painted in chalkboard paint. Students could write the question, and then throughout the week other students could write their replies, and their replies to others' replies. (This doubles as an authentic chance to practice elegant lettering.)

- Commission a student to find an answer. Imagine, here, each class as its own Royal Society: funding exploration to solve the most tantalyzing gaps in knowledge. At the end of the week, the student could issue her report in a brief speech — 4 minutes, say, outlining how she pursued the answer, and what she found.

- Share the question with the wider community. We could, for example, ask other classes their opinions, or the faculty. Or we could ask the classroom parents. Or we could ask a few particular community specialists — a rabbi, perhaps, or an engineer, or a city councilperson. (Skype could perhaps help here.)

Our goals:

We hope to...

- Knit together a community through shared quests.

- Invite debate when everyone can't agree to an answer.

- Learn a whole lotta cool stuff!

- Develop some mastery at research. (Commissioned students could have practice using Google, Wikipedia, print encyclopedias, and — gasp! — an actual library full of books.)

If you walk into our classrooms, you might see:

If you waltz into one of our classrooms, you might spy a pair of students earnestly debating a policy issue — like whether a lowering of the drinking age would be worth it. Or you might see a single student giving a slick 5-minute presentation on what plants eat (hint: the Sun). Or you might see a whole class interviewing someone about history — like asking a veteran whether the United States should have invaded Afghanistan.

Some specific questions:

- When I was in high school, we sometimes had to write papers answering some specific question. Only rarely did I especially care about the question I was supposed to answer. Students should spend their time answering questions they actually care about.

- That last point wasn't actually a question. The real question: isn't this cool?