Yesterday, we went to an ADVENTURE PLAYGROUND! I first ran across the notion of an "adventure playground" in architect Christopher Alexander's watershed book, A Pattern Language. In it, he writes:

A castle, made of cartons, rocks, and old branches, by a group of children for themselves, is worth a thousand perfectly detailed, exactly finished castles made for them in a factory.

I think this strikes many of us as perfectly apt: our culture glorifies a certain DIY-ness among young children. We romanticize the good ol' days when kids were afforded more freedom than our helicopter-parenting age allows.

If you don't have time to make a fort when you're a kid, well, when do you have time to make a fort?

Alexander goes on:

Set up a playground for the children in each neighborhood. Not a highly finished playground, with asphalt and swings, but a place with raw materials of all kinds — nets, boxes, barrels, trees, ropes, simple tools, frames, grass, and water — where children can create and re-create playgrounds of their own.

Adventure playgrounds are rare in the United States: Wikipedia lists just five of them. Delightfully, one is 20 minutes from our apartment — oh, the perks of living around Seattle!

Here's what we found!

As we entered, our kids were given a box of tools (containing hammers and nails, screwdrivers and screws, tape measures, levels, etc.), and an optional safety goggles and hard hat:

And then we entered what I can only describe as a magical shantytown: a grove filled with the zany forts and citadels constructed by successive waves of children.

At the summer's beginning, the grove was empty — kids and parents built up structures little by little over the three months. One of the only rules is that while you can add to what others have built, you can't tear anything down.

When you're two, there's something liberating about wielding a hammer:

Even we parents got into the fun:

I saw older kids adding more elaborately to the various structures. Near the end of our sojourn here, our 5-year-old decided to build something a bit more simple: a teeter-totter.

Simple, but boy, was it deligthful!

He and I had a blast experimenting with gravity. I'd stand at one end, and he'd see if he could lift me off the ground — by jumping, by moving the fulcrum, by asking me to come in closer...

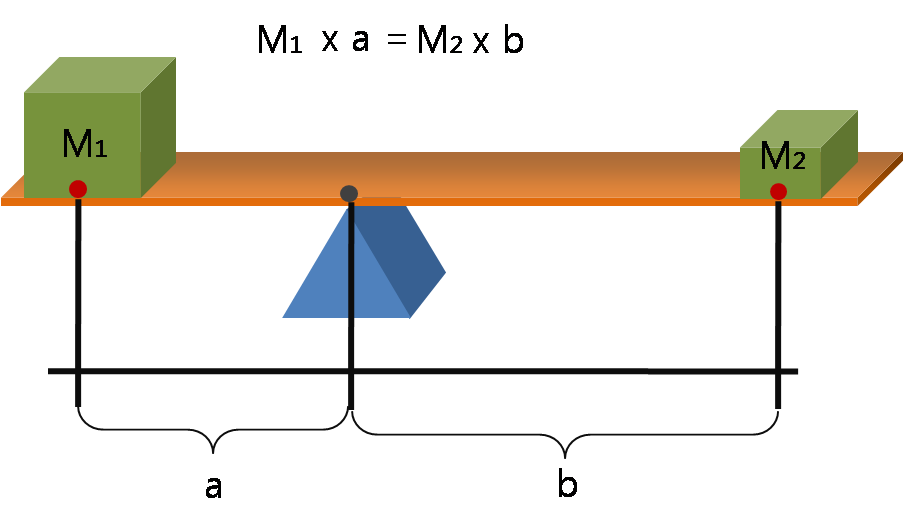

Now, we could talk about levers abstractly, using diagrams and algebraic variables:

... but he's only five. (Well, he'd insist five and a half.) We can safely postpone those — right now, it's more important to get an embodied understanding of how levers work. Later, when he engages physics formulae, he'll do so with intuition on his side.

Other than early physics education, why are we so excited about pursuing having adventure playgrounds attached to our schools?

We could list a host of reasons:

- developing skill with manual tools!

- nurturing a maker's mindset!

- getting that hard-won sense of personal awesomeness that comes from building something!

Today, though, I'd like to focus on what might be the most important reason of all: danger.

I'll state this plainly: kids need danger.

Yesterday, at another corner of the park (far away from the adventure playground), Kristin fell into conversation with another mom —

Kristin: Good gravy isn't that adventure playground great?! Other mom: I don't know... it sounds a little dangerous. Kristin: Yes! Dangerous! Absolutely! That's the point!

Most American children, in the present era, don't experience much danger.

Obviously — this should go without saying, but it's the Internet, so one must be explicit — obviously, we don't want to plunge our beloved children into profound danger. We don't want them to lose limbs, poke out eyes, or have brain damage.

But I suggest we do want them to scrape their knuckles, bruise their butts, and occasionally thwack their thumbs with hammers.

Why?

Hannah Rosin explores this brilliantly in her 2014 Atlantic article, "The Overprotected Kid".

Ellen Sandseter, a professor of early-childhood education at Queen Maud University College in Trondheim, had just had her first child, and she watched as one by one the playgrounds in her neighborhood were transformed into sterile, boring places.

Sandseter had written her master’s dissertation on young teens and their need for sensation and risk; she’d noticed that if they couldn’t feed that desire in some socially acceptable way, some would turn to more-reckless behavior.

She wondered whether a similar dynamic might take hold among younger kids as playgrounds started to become safer and less interesting.

Humans seem born with an urge to experience danger. The strength of that urge seems to vary quite profoundly: I was a skittish kid; my son seems to crave peril. (My wife and I joke that our image of him at age 16 is on a dirt bike, holding a beer, at the top of a flight of stairs.) Vive la différence!

If we don't experience a danger when we're young, some of us will seek it out.

If we don't provide a little danger, we're putting our kids at risk of greater danger.

Rosin again:

In 2011, Sandseter published her results in a paper called “Children’s Risky Play From an Evolutionary Perspective: The Anti-Phobic Effects of Thrilling Experiences.”

Children, she concluded, have a sensory need to taste danger and excitement; this doesn’t mean that what they do has to actually be dangerous, only that they feel they are taking a great risk. That scares them, but then they overcome the fear.

That is: Children need fear to grow into fearless adults.

If we want our kids to mature safely, we should find opportunities for danger.

That adventure playgrounds allow children to moderate their own risk seems crucial. If a child is still skittish around heights, they can start by sticking to the ground, and engage heights gradually. If a child is worried about thwacking their hand, they can start by avoiding hammers altogether, and try hammering only when they're ready.

Small, repeated exposures to risk, directed by the children themselves, can lead to being comfortable with real life.

Rosin looks at some of the details Sandseter found:

In the paper, Sandseter identifies six kinds of risky play:

- Exploring heights, or getting the “bird’s perspective,” as she calls it—“high enough to evoke the sensation of fear.”

- Handling dangerous tools — using sharp scissors or knives, or heavy hammers that at first seem unmanageable but that kids learn to master.

- Being near dangerous elements — playing near vast bodies of water, or near a fire, so kids are aware that there is danger nearby.

- Rough-and-tumble play — wrestling, play-fighting — so kids learn to negotiate aggression and cooperation.

- Speed — cycling or skiing at a pace that feels too fast.

- Exploring on one’s own.

This last one Sandseter describes as “the most important for the children.” She told me, “When they are left alone and can take full responsibility for their actions, and the consequences of their decisions, it’s a thrilling experience.”

There's so much more to talk about with this issue: how would we handle bigger safety concerns in a school-run adventure playground? How do we handle the ever-present threat of litigation? How can this interact with our desire to reduce levels of depression and anxiety in young adults?

If you'd like to probe our thoughts about those (or other) questions, shoot me an e-mail!

But I'll end by stating the basics: that we're making schools for humans means a lot of things, but foremost among them is that we're redesigning schools to match with the obvious facts about what students are. And so we want to bring adventure playgrounds into the school experience. Because:

Risk can lead to well-being. Danger can lead to flourishing.

My thanks to the wonderful crew working at the Mercer Island Adventure Playground — and to the city of Mercer Island for making this happen!