Where does everything come from?

This is how our new kind of school has started off our year of Big Spiral History: by telling stories about the creation of the world.

That's stories, plural. Whose stories, you ask? As many peoples' as possible!

In order: we're teaching the Norse story, the Greek story, the Hebrew story, and the Ojibwe story. That's our first week.

(This is, of course, the cow that emerged from the primordial ice to nourish the first of the frost giants. Y'know, the bad guys in Thor? It's a pretty generous cow.)

Then, we're telling the creation stories of the Chinese, the West Africans, the Maya, and the Aborigines. That's the second week!

And the third week, we're slowing down to tell just one creation story: that of the Big Bang, and the evolution of multicellular life, up through us humans.

Go ahead: ask why!

First off, we're beginning at the beginning: the dawn of Life, the Universe, and everything.

The way that history is typically begun in schools, we think, is foolish. I've criticized this before, but the long and short of it is this: in grade school, kids don't begin with the beginning. Rather, they begin with the close at hand: their own selves, their own neighborhoods, their own cities. They're plopped in the middle of reality, and are held back from looking at the big picture.

This approach is designed around an outmoded theory of children's reasoning — that they can only understand things that they've actually experienced. (How these old theorists would have explained children's lust for a certain movie series that begins A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away... — well, that I'd love to know!)

By the time the curriculum gets around to talking about any beginnings, it's already middle school. And the beginnings don't go back far at all — mine went back only to the Fertile Crescent. Fail! The Fertile Crescent was one particular origin of "civilization" — that is, city-centered state-level society — but not of humanity, in general.

And the origin of humanity? And of life? And of anything? Those are thought to be scientific questions, not historical ones. They're not part of the story of humanity — they're held apart in another class.

Which, of course, is ridiculous. Drawing a sharp delineation between "questions of history" and "questions of science" might have made sense two centuries ago, but at the start of the 21st century it's just foolishness.

The humanities and sciences have linked up, and we now possess an all-but-seamless narrative of all of cosmic history. This is the result of decades of daring acts of research — it's one of the great successes of human intellectual life!

Your atoms were forged in a supernova.

The oxygen you just sucked in was breathed by Triceratops and Velociraptors.

Life blooms, proliferates, and adapts.

And you're part of it: your amazing qualities are the inheritance of millions and billions of years of biological experimentation.

But we don't let this paradigm shine in the curriculum. We don't use it to orient kids, and invite them to ask the big questions.

Instead, we bury it.

So the first reason we're doing this mad-rush through creation stories, is to follow the advice the King in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland:

Begin at the beginning, and go on.

It's only sensible.

We're beginning at the beginning: the Big Bang, and all that.

But why all the other creation narratives?

(Note: this is contentious. Political, even! We Americans love to hate each other's views on this. And, according to various polls, we're about equally split — 50% think the universe is about 6,000 years old, and 50% think it's about two million times older. I'll be treading boldly into this fray — but I hope, also, politely and kindly.)

So why are we starting the year with multiple creation narratives? Well, a host of reasons, actually!

- We want to introduce kids to the awesome mystery of where the Universe comes from. (Approaching this question from a multitude of previous attempts helps kids appreciate the mystery.)

- We want to expose kids to a multiplicity of human cultures and their stories. (Think of each story as a hand-shake to a culture they'll be hearing more about later.)

- We want to help kids see that stories matter — that where we think the world comes from can inform how we think about ourselves. (Stories — origin stories in particular — shape worldviews, and worldviews shape lives.)

- We want to get kids used to the idea that differences of opinion are the norm, and that they can be fertile grounds for great conversations. (A disagreement is a great opportunity.)

In my mind, though, there's one great reason that we're starting by luxuriating in a multiplicity of creation stories: to make kids question our authority when we tell them something is true.

In our schools, truth is rarely — if ever — handed down on authority.

If people in the real world disagree about something, then it's not our job to pick a side and tell the kids to swallow it. Rather, our job is to expose kids to multiple viewpoints, and help them reason through them.

Perhaps I'm speaking too blithely here — perhaps I'm coming across as if I think our schools should champion every idea equally.

No — quite the contrary! What I'm saying is that our teaching shouldn't champion specific ideas at all.

What I'm saying is: science.

There is a world outside our heads. We can approach it through observing carefully, interpreting carefully, and concluding humbly — and then inviting criticism of our conclusions.

A shorthand for this: the scientific method.

We're starting our school by putting all creation stories on an equal footing. We're not ending there!

All of the above, I think, would be a bad approach if it were performed in a school that simply Delivered Answers. But ours is not — we pose questions, we hunt for answers, we practice science and philosophy continuously. We splay ideas on the wall; we sit in mysteries and slowly unravel them.

I'm not advocating this curriculum for most schools: I'm announcing it for ours.

Allowing the world's true diversity of hypotheses to be considered honestly sets an important standard: we are a kind of schooling that is willing to ask the big questions, and to help children form their answers thoughtfully.

And it's hard to do this with just one story. Differences spawn productive thinking! But setting up just two stories leads to tribal warring — "you're either with us or against us!" What we need is a plurality of stories.

I'll pause here to acknowledge something obvious:

Some of our parents will be evolutionists who fear (quite legitimately) that the scientific narrative will be lost amidst the flush of other origin stories.

And others of our parents will be creationists who fear (quite legitimately) that the Genesis account will be lost, too.

I owe answers to both groups of parents. And here it might be useful to disclose my own origin story. I'm convinced the story of Darwinian evolution is true — but I didn't used to be — and the story of how I got from there to here is a bit unusual.

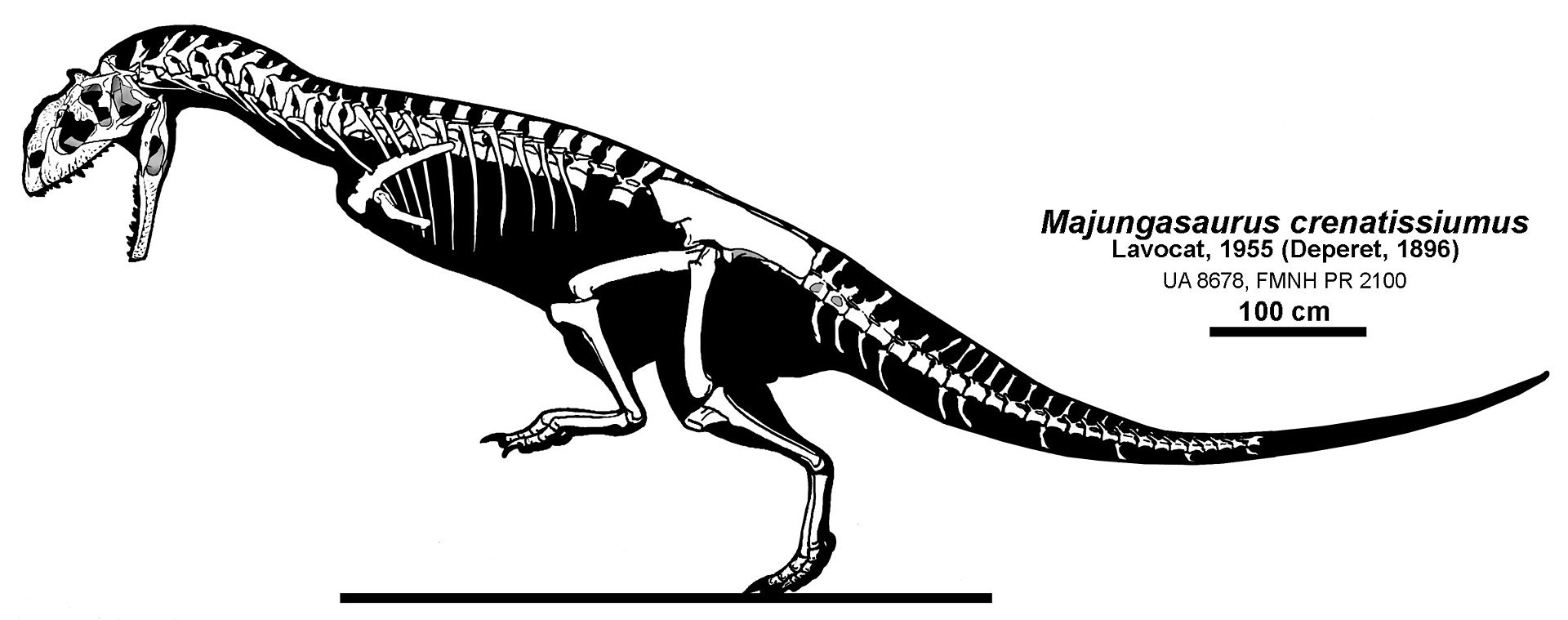

I grew up in an evangelical home, but my childhood intellectual life was shaped more by dinosaur books than it was by Sunday school. (I was a dinosaur fanatic. Still am, sorta!)

I only became a creationist in 8th grade, when my (public school) science teacher decided to transform our classroom into a courtroom, and to put the theory of evolution on trial.

He himself, I believe, supported evolution. And I think he thought the evolution side would come out as the obviously true one.

He picked me to lead the prosecution: to argue against Darwinian theory.

And, as a result of that, I became a creationist: not because I was indoctrinated into it, but because I became convinced of the evidence.

(Note: looking back on this, the evidence against evolution that I was looking at was really terrible stuff — since then, I've seen many creationists criticize it, and criticize fellow creationists who use it. The much-mocked "teach the controversy" idea, I think, really is fantastic — but only in an environment in which kids are helped to develop a B.S. detector. Our schools can do this — and, I think, are!)

After we finished the debate, I kept reading. (It really was interesting stuff!) And, slowly, my conviction that the world was made six thousand years ago faded. The arguments (even the better ones) really weren't that strong. When I looked deeply into them, they were convoluted and riddled with holes, and seemed to depend on giving lots of weight to oddball discoveries — for example, what might be a Mesozoic-era human footprint, if you squint just right.

The arguments for evolution, meanwhile, seemed straightforward and robust. Given what we knew of DNA (and math), it seemed impossible that evolution wouldn't happen. And the evidence was everywhere. I realized, at some point in my freshman year of high school, that the earth almost certainly was very, very, very old, and that natural selection was the best way of explaining the evidence — maybe the only way.

And so I became an evolutionist.

I came to my conviction the old-fashioned way: through personal exploration, helped along by a community of people. (Though, in my case, the community was mostly people who wrote books, and who posted online.)

I think this is a much better way to become convinced of evolution. Why? What does it matter how one becomes convinced of some truth of the world?

One reason is that approaching truth through doubt and exploration made me humble in my beliefs. I recognize that I've changed my beliefs before; I'm likely to do so again!

I said a minute ago that I'm an "evolutionist". I hate that word: the -ist suffix makes it sound like evolution is something I "believe" in. I suppose I do, under certain definitions of "belief" — but what's wonderful is that I'd upend these "beliefs" in a heartbeat if I found good evidence to the contrary.

This is a better way to hold a "belief": humbly, and carefully. The strange thing is that such beliefs aren't weak: they're actually very strong and resilient.

A second reason I think it's better to come to true beliefs through doubt and exploration: doing so allows you to see beliefs from the inside. And when you do, you see why people love them.

I don't think the Genesis story is true — but boy, do I love aspects of it!

Genesis paints a picture of original harmony — humans didn't slaughter animals; animals didn't even slaughter other animals! Pain and suffering weren't originally part of humanity — a state we can perhaps strive to reach again. And humans were designed to be careful stewards of the natural environment, not exploiters.

So often, in online debates, evolutionists portray creationists as stupid. What they fail to see is that creationism is a beautiful poem — one that can have wonderful implications for how we structure our society.

Our schools don't only seek to immerse kids in good scientific reasoning — they seek to make kids better at understanding all humanity.

Here's another reason I think it better to come to true beliefs through doubt and exploration: by doing this, I became acquainted with what in-depth understanding feels like.

Exploring creationism and evolution meant learning a lot of science — paleontology, biology, geology, and some chemistry and physics.

Even better, it meant appreciating what really is good evidence and good reasoning — and what only seems to be.

I'm a deeper knower now — a much more careful knower — than I would have been without this.

Sometimes, when I feel really passionately convinced of something else (say, some political idea), I'm able to reflect on how that feels different. It feels ungrounded.

I'm not saying, of course, that our schools should lead kids through false beliefs before they get to true ones. (What an effort that would take!)

And I'm not saying that in-depth understanding can only come from leading kids through wrong theories. (Our Learning in Depth curriculum in particular will also aim to develop this sort of understanding.)

I'm only saying that, when a student believes anything to be true without good reason, we should be delighted for the opportunity to patiently lead them through thinking about it. Because on the other side of that patient reasoning lies actual, hard-won wisdom.

This is part of what good teaching is. We should look for more opportunities to cultivate it in our curriculum.

So what can I say to parents who fear the scientific narrative will get crowded out? Just this: that it's only when the scientific narrative is placed amidst the earlier narratives that we can really appreciate what makes it wonderful.

And what can I say to parents who fear the Genesis narrative will be crowded out? Just this: that in most public and private schools, the Genesis narrative is entirely ignored. And in evangelical schools, it is believed woodenly and thoughtlessly (something many evangelical thinkers are critical of). Both of these approaches are tragedies. The Genesis narrative deserves to be taken seriously, both scientifically and poetically. And the role of teachers in our school is not to direct students to this or that belief, but to help them think carefully about all beliefs.

There are, maybe, two other reasons I'm happy to not only tell just the Big Bang story of creation by itself.

First, this doesn't result in accurate belief.

Last summer I went to a presentation by evolutionary scientist Steven Pinker. He talked about how about half of Americans don't believe in evolution. That's bad, he said. But there's something that's worse: that most of the people who say they believe in evolution don't actually understand what evolution is.

"Believers" in evolution tend to think it's goal-directed, Pinker said. That organisms are trying to evolve "upward".

What they actually believe in isn't natural selection — it's something that more closely resembles the medieval "Great Chain of Being".

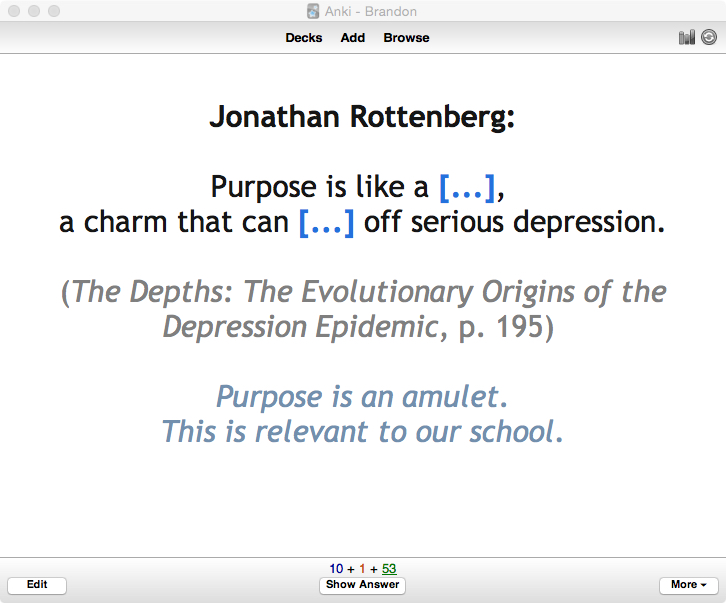

If you want people to understand evolution, I suggest, help them try to attack it. Help them be skeptical. Help them construct their own understanding of it — and point out where things don't make sense.

Second, telling the Big Bang story by itself — in a culture that believes lots of things (from young-earth creationism to alien intervention) — sets up a very stupid sort of rebellion.

As a teacher, there's something that terrifies me about many of my high school students:

They're so prone to conspiracy theories.

Aliens, Bigfoot, evil government cabals that encourage vaccinations to murder people and keep the population down — you name it, I've seen kids believe it — worse, zealously adhere to it, even in the face of obvious, overwhelming evidence to the contrary!

And why are they so difficult to convince otherwise? Well, many reasons, no doubt:

But one big reason seems to be that they see themselves as the rebels. They're stuck in a framework that sees common sense as "dominant, corrupt opinion" and see anyone who departs from it as a freedom fighter.

"Hey, I'm just being skeptical", it seems like they're saying.

No, they're not. They're being the opposite of skeptical: they've picked an opinion, and are zealously clinging to it against evidence.

They haven't realized that being skeptical means, among other things, being skeptical of yourself. As physicist, samba-player, and all-around-amazing-human-being Richard Feynman said in a commencement address:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.

The way to teach evolution is to start by teaching it along with other stories, and to keep coming back to the question, "How would we know if any of these is true?"

And this turns out to also be a great way to get kids interested in many human cultures.

And to enjoy telling some awesome stories.

That's not it for our first few weeks of Big Spiral History — and it's certainly not it for teaching about the creation of the Universe (no, seriously — where does the Universe come from? what happened before the Big Bang?), nor about Darwinian evolution.

But this is a great place to pause, and seek out clarifying questions. Obviously, certain online communities can get pretty red in the face when it comes to talking about origins — I'm hoping that we can use a bit of that to help us fine-tune how we engage students in these questions.

One question on my mind: Is there a danger in our schools becoming too relativistic? What else would need to come later in the curriculum in order to avoid this?

A second question: does any of this run afoul of the church/state divide? Though we're starting this new kind of schooling with two private schools, we have our eye on eventually starting some charter schools. The church/state question isn't relevant for now, but it might be, later.

So, if you've got questions as to how, exactly, we're going to pull this off, please ask them! Join the conversation on our Facebook page. (And like us, to get updates!)

We're creating a civil community, and any posts that smell of dissing "the other side" will be deleted (ah, I'm sorry I even have to say that, but: the Internet!).

But every other piece of commentary will be appreciated, and considered!